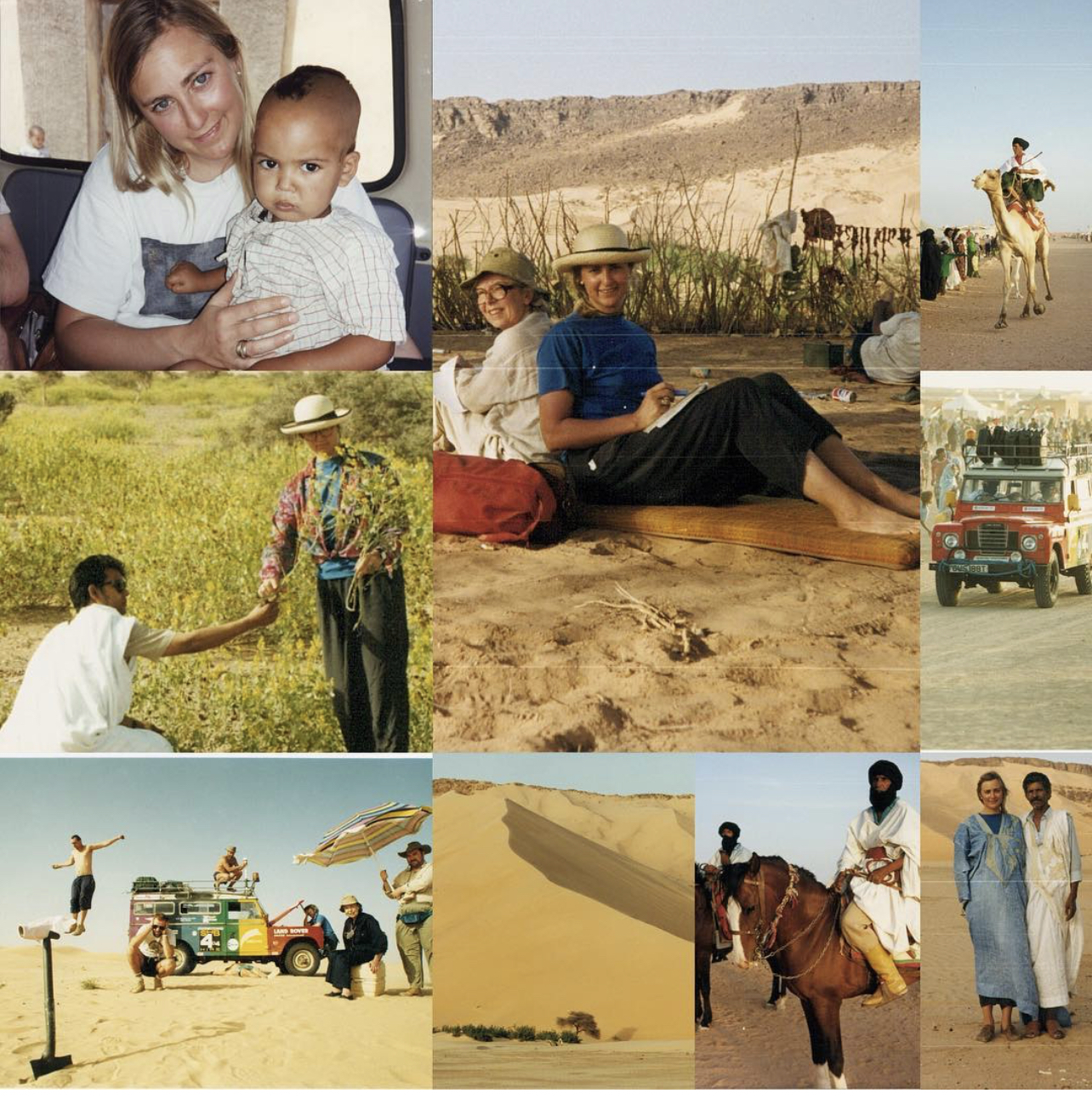

Following a BOAC plane crash in May, 1952, two pilgrimages were made to the Sahara desert to remember those who bravely battled to stay alive in the fierce heat. Just over 30 years ago, Today newspaper editor Martin Dunn assigned photographer David Hill and myself to accompany British widow Olwen Haslam on what was her first trip to Mauritania to search for the grave of her husband CoPilot Ted Haslam, who died after head injuries resulting from the crash. Ten years after our expedition, my dear brave friend Olwen returned at age 78 with photographer David Hill, our expedition leader Robert Watt and the last survivor of the crash – Richard Gurney. This is Olwen’s story: a story of sun, sand and love. It is a story that over the years, I have been blessed to have shared with her, and David.

Photo: © David Hill 2002

When the sun rose on the wrong side of the plane, Trevor d Nett, the navigator of the Hermes, knew that he and the 17 others on board a routine flight from Libya to Nigeria in May, 1952, were in trouble. Until then, he was sure the plane was travelling south, and confidently, expected to look to his left to see the sunrise. Instead, the sun rose behind the plane and only then did De Nett become aware of the horror of the situation. The plane was 1,300 miles off course, dangerously low on fuel and with nothing below but the sands of the Sahara stretching to the horizon.

A series of frantic SoS signals were sent out to no avail and pilot Robert Langley was forced into a crash landing in the dunes. Every one of the eight crew and ten passengers, including a six-month-old baby, survived the landing.

However, their remarkable escape from the wreckage was just the start of their battle to survive in temperatures of up to 50C. They were stranded for four days at the crash site before making the trek to an oasis 15 miles away. The rigours of the journey proved too much for first officer Ted Haslam, who died shortly after reaching the safety of the oasis.

Their remarkable story might have been forgotten but for the efforts of Robert Watt. An advisor on Michael Palin’s Sahara BBC TV series, Robert has been obsessed with the desert since he was a boy at Robert Gordon’s school in Aberdeen, Scotland.

“I’ve always been drawn to the desert,” he said. “From the first time I saw the film Lawrence of Arabia, I was overcome with a determination to go there, myself.”

Photo: © David Hill 2002

Robert has since made more than 40 trips to the Sahara and spent over a decade planning an expedition to salvage the remains of the plane for the Imperial War Museum near Cambridge, UK.He was determined that the G-ALDN Hermes – “a mastery of British technology” with four 2,000 horsepower engines – should not be swallowed up by the desert.

“I first became fascinated by the story when I led an expedition taking Ted’s widow Olwen Haslam to see her husband’s grave in 1991. Seven years later I located the crash site. Looking for the plane was like searching for a needle in a haystack and it was only because I have a large pool of local contacts there that I was able to find it. Amazingly, Hadaraminie, the nomad who helped me, told me his grandfather was one of the three Bedouins who helped the survivors and gave them shelter.

“Back then, the plane’s bulky fuselage was largely intact under the encroaching sand, and being put to good use by a local tribesman as a rather novel storage place for his possessions.”

The luxury Hermes had large seats and a powder room for the ladies. The Handley Page aircraft was built to make long-distance travel a pleasure and it was later discovered that the Hermes crisis was due to human error. Trevor De Nett, who was a trained pilot but not a qualified navigator, had inadvertently set the plane on its treacherous path at the outset of the fight when he input the wrong compass variation figures.

Robert Langley, the plane’s captain, compounded the error by ignoring procedure and steering the plane on a C12 compass alone, backed up by dead reckoning and astro-fixes from a periscope sextant.

Robert Watt employed an army of 17 local workers who toiled for ten days under the blistering sun, digging trenches, criss-crossing the dunes and shovelling away tonnes of sand. Their hard work paid off when the plane’s escape hatch and the four engines were unearthed.

“It was hugely satisfying to find the escape hatch and amazing to think this was the very door that the survivors had come out of in the 50s,” adds Watt.

The youngest survivor, the then six-month-old Richard Gurney, was with Watt on the last expedition to the crash site in Mauritania, West Africa.

I had tracked down Richard to his home in New Zealand and so had Robert Watt, who asked him to take part in a BBC documentary about the Hermes.

Richard said he felt strangely moved when he first laid eyes on the emergency exit: “It was difficult going back and reliving things that happened in my life that I was not even aware of before. I’ve been out there in the searing heat, and I know how tough it is. Unlike our expedition, they were out there in the middle of summer, and I know now what hardship faced. They had precious little water and what they had was poor quality. Going back had a big effect on me. At the time, my father Frank worked in Nigeria as an electrical engineer. We’d been on holiday in the UK and together with my mother Enid were returning to Kano when we were involved in the crash. No-one was prepared for anything like that. It must have been sheer torture.”

There is no doubting the difficulties the survivors faced – but they did it in particularly British style. Shaken but relieved to have survived, in the immediate aftermath of the crash, pleasantries were soon exchanged and the cabin crew set about making cups of tea. Their baggage was used to form an SoS in the sand.

Help first arrived in the shape of three Bedouin nomads on camels, who erected their tents to provide shelter from the burning sun. More relief followed when a rescue plane flew overhead. A French medical team parachuted down and tended to the wounded. Medical packs and a portable radio were also dropped off.

Morale was lifted with news that a rescue team was on its way. In fact, their ordeal had barely begun. Four days on, they learned that the French rescue vehicles could make it no further than an oasis 15 miles away. It was then decided that the survivors had no option but to make the journey there by foot and on camel at night to avoid the heat.

During the trek through the desert, the group endured a 90-minute sandstorm. Sixteen hours after leaving the crash site, Captain Langley insisted the group stayed put, but chief flight attendant Len Smee went on ahead to find help.

Eventually, he spotted the rescue team and was able to point them in the direction of the stranded survivors and in turn they showed him the way to the oasis. It was a sad irony that after reaching the oasis at Aioun Lebgar, first officer Ted Haslam, 30, died. He was buried there under a makeshift wooden cross, which has since been replaced with a granite headstone, which was erected at a sacred burial site.

Two months after the crash, the captain and navigator were dismissed by BOAC after an inquiry and chief steward Len Smee received a commendation.

Richard feels no resentment or blame towards the captain or navigator, only a sense of how lucky he was to have survived.

“There was so much to take in,” he adds. “I’d never given it much thought before. I spent a lot of time there, not saying much, just thinking about it all.”

Meeting Ted’s widow Olwen, then 78, had a profound effect on him. Olwen, who had first visited Ted’s grave ten years earlier in a trip that I was fortunate to accompany her on, was able to introduce Richard to the tribal leader Sidi at the oasis. Sidi remembered Richard as a baby and was able to describe the moment the group staggered in from the desert all those years ago.

Richard produced a gleaming tea pot – a souvenir from the crashed plane which his mother had brought back from the desert. Until then, the silver pot had been among the few clues to his past adventure, and in a lighter moment once they returned Olwen, Richard and I enjoyed a cup of tea from it at Olwen’s home in Kensington, London.

“The most poignant time was being at the grave site with Olwen,” said Richard. “She is a remarkable woman and devoted to Ted. I helped tidy up the grave and Olwen asked me to read from the Bible. It was very emotional. What was running through my mind was that Ted hadn’t survived and all the rest of us had. It could easily have been the other way around.”

Olwen, who had only been married to Ted for nine months, said at the time: “Some of my friends thought I was potty to make the long journey out there again, but I wanted to visit Ted’s grave one last time. It was very moving standing there alongside Richard. I remember seeing his picture in the newspapers as a baby, and I’d always wondered what had happened to him. I was also delighted to see Sidi again, and I know that with him around Ted’s grave will be kept in order – that gives me immense comfort.”

As expedition leader, Robert Watt says he was anxious to ensure Olwen’s health and safety in such a harsh environment. “She had to travel by camel, just as some of the passengers did, because the nearest vehicle access point was five miles away. She arrived after dark to avoid the heat. And her time at the crash site was reminiscent of the conditions endured by the survivors, with the rationing of water supplies, which had to be carried in by camel.

“Along with the rest of the expedition, Olwen slept out on the sand under desert stars because the tents were insufferably hot. She experienced a light sandstorm when she was sleeping out.”

Olwen said she was nervous about visiting the crash site to begin with, adding: “I wanted to know the whole story. Although it was difficult – I knew in a way it would help settle my mind and it has.”

The trip gave Richard a clearer picture of his mother Enid, 30, who was killed in a road accident a year after the plane crash. “It helped me to come to terms with what happened. It’s the closest I’ve ever come to knowing her. She must have been very brave to have coped. I know she was breastfeeding me at the time, and, according to Len Smee whom I met in England, I was a very quiet baby and hardly cried. I was definitely the priority, and my mother and I were among those who rode to the oasis on the back of a camel.”

One a personal level, the trip was successful although the salvage operation didn’t go as planned. “Sadly, we arrived to find only a few remaining remnants of the plane: notably one of the escape hatches, four burnt-out engines and the nose-wheel assembly. Despite probing the dunes with eight-foot steel rods and searching for signs with a metal detector, the fuselage was never found.”

Robert Watt was hugely disappointed not to find the fuselage, but was pleased the story of the Hermes was told. “The BBC documentary aired on the 50th anniversary of the crash, and I knew if it wasn’t told then, it never would be. Later, it was learned that an opportunistic merchant from the distant town of Atar had arrived two years earlier, with a camel train loaded with wood. He had set fire to the plane and melted it down into manageable transportable lumps, to be taken back to ‘civilization’ for recycling. “Ironically, he was probably alerted to a money-spinning opportunity because of my frequent trips to the crash site. It’s a shame we lost an important part of aviation history, but on the other hand, it’s the ultimate recycling and it’s being put to good use in the community.”

Postscript: Olwen Haslam was in her 90s when she passed away only a few years ago. From our journey in the desert, we forged a special friendship and I think of her often. The last time I was able to visit Olwen she told me she was planning to reach out to Robert Watt and ask him to spread her ashes over Ted’s grave. To this day, I do not know if this happened but I like to think of Olwen with Ted together. After Ted’s death, Olwen never remarried.

Postscript 2: My friend David told me that he was willing to travel to Mauritania to take Olwen’s ashes and bury them with Ted at the oasis we visited together all those years ago. Sadly, I was unable to go because Mauritania is known to be the most dangerous place on the planet. However, I was able to liaise with her family to help make Olwen’s final wishes happen. Now I can rest in peace that more than 70 years since they said their last goodbyes, they are now together at this beautiful oasis in far flung Mauritania. RIP Olwen, my friend.