Australians are pretty big consumers, but it wasn’t that long ago that we knew nothing about the vast array of products we use on an everyday basis. Consumer advocacy was something that only got going in the 1950s and 1960s; sustainable use of raw materials and ethical sourcing are ideas that have come to us very late – it’s only been a live issue for the past 10 years.

For many years we were using products whose source we didn’t know, whose manufacturing and workplace methods were opaque, whose depletion of vital raw materials was never queried and whose safety was never called into question.

Before consumers advocates there was nothing – except lone crusading individuals. How, for instance, do we know about the dangers of asbestos? In the early to mid 1970s, Henri Pezerat, a toxicologist, sought to make the French government, trade unions and public aware of the horrific legacy asbestos had left in his country. His work was ignored, ridiculed and sometimes dismissed as the ravings of a leftist troublemaker, but without him we wouldn’t know that our very houses were death traps.

Remember the controversy over Nike sweat shops in South-East Asia? How did we learn what was really going on? In 2000, Jim Keady went to Indonesia and stayed in a slum with Nike workers. He survived on $1.25 per day and told the world about forced overtime, starvation wages, sexual harassment, physical violence and intimidation by supervisors. Again, one man took up the struggle and we are the better for it.

Men like Keady and Pezerat had to fight vast vested interests whose industries were pumping out popular commodities. My own personal hero harks from much further back. His name was Walter Hardenburg. The man who blew the whistle on rubber.

Yep, harmless rubber. Back in the early 20th century, when Henry Ford’s model T stormed onto American roads and bicycling was all the rage, rubber was more expensive per pound than silver. The West wanted rubber bicycle and car tyres, rubber hosing, garters, women’s hosiery, prophylactics and medical equipment. Industry needed it for engine belts and to cushion moving parts. The demand for rubber was insatiable.

The problem was the best rubber grew in the wilds of the Amazon. You couldn’t cultivate it. Rubber workers had to painstakingly locate and tap solitary trees which slowly dripped small amounts of rubber sap per day. To get the volumes the rubber manufacturers needed, the industry needed an army. Without the labour willing to work in the insect-infested forests of the jungle, there was only one source of labour – the native populations. The rubber barons set out to enslave them.

The rubber barons started by saying they were an honest, civilising presence up against blow-gun wielding natives who would cannibalise them if given half the chance. They set about demonising the people they intended to enslave, thereby justifying what they “had to do”. Natives who resisted these ‘civilising’ bosses were set alight, castrated, dismembered or beheaded. Native women were kept in breeding corrals, sired by white masters whose only intent was to build a race of rubber workers. One story was told of a would-be concubine who refused to be a breeding vessel. Her penalty, the story goes, was to be fired from a cannon.

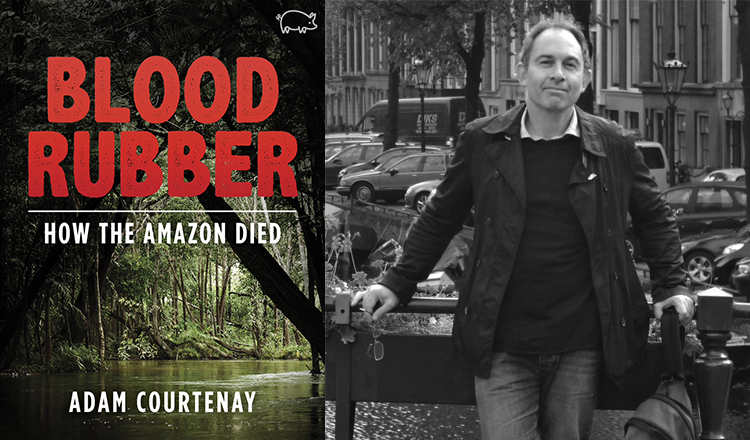

Adam Courtenay

This was where the rubber came from – a place of foul water, insect clouds, death by beri-beri, yellow fever and malaria, where jaguars and anacondas dwelt and where a notorious vapour bath would regularly descend, causing biscuits to sprout whiskers and gun powder to turn into syrup.

Walter Hardenburg, a 21-year-old American engineer who just wanted to do a bit of hunting and fishing in the jungle, walked straight into all of this. He could have walked away but he chose to stay and document what was going on. He was an accidental crusader. The information he eventually took to London about the obscene working conditions and violent methods of rubber extraction caused an international outcry.

Blood Rubber is about the industry, but it is also about human nature. It is about how we can so easily turn a blind eye to horror if carrying on that horror suits us. But it is also about human greatness in the face of almost impossible odds. Hardenburg’s story is that of the power of one versus the power of the machine, the heart of darkness versus improbable goodness – a story too important to be lost in the tropical miasma. It stood out even in the vastnesses of the world’s greatest jungle, because everyone, in some way or another, was involved.

Adam Courtenay’s ebook, Blood Rubber – how the Amazon died is available as a Kindle Single on Amazon.com. To get a copy of Blood Rubber (for only $US2.99) click here.

About Adam

Adam Courtenay is an Australian writer and journalist who canoed up the Amazon as part of his research for this book. He has trekked some of the world’s most enthralling and difficult trails: retraced Hannibal’s footsteps over the Alps; slogged over the Kokoda Trail in New Guinea; and walked the Aboriginal Larapinta ‘Dreamtime’ in the central Australian desert. He currently writes for The Sydney Morning Herald/Age and is the Australia correspondent for the online finance platform TradingFloor.com. He lives in Sydney, Australia.