In this extract from Lonely Planet’s Guide to Death, Grief and Rebirth, author Anita Isalsk shares the fascinating truths about catacombs and ossuaries across the world.

From Roman-era mass tombs to the ‘bone art’ of ossuary artisans, these places have a meaning that transcends their function as mere skeleton depositories.

The first official catacomb was the system of underground tombs along Rome’s Appian Way. Roman law forbade the burial of bodies within city limits – a sensible regulation that had been disposed with by medieval times, leading to untenable situations like that of 17th-century Paris, where city-centre burial grounds posed a real risk to the wellbeing of citizens.

Underground tunnels and crypts – either purpose-built or reclaimed – became an expedient and elegant solution to the problem of excess skeletons. (A lexicographical note: a catacomb is underground, while an ossuary is simply a place where bones are kept.) While at heart an operational affair, these realms of bone often take on deeper significance.

As grand-scale memento mori, they remind us of life’s fleeing nature, that in death we are all alike. As an engraving in the Paris Catacombs says: ‘So all things pass upon the Earth / Spirit, beauty, grace, talent / Ephemeral as a flower / Tossed by the slightest breeze.’

Sedlec Ossuary

An unprepossessing chapel beneath the Cemetery Church of All Saints in Kutná Hora, about 56km (35 miles) east of Prague, is perhaps the world’s most celebrated ‘bone church’. The story begins with a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. When a local abbot returned with holy soil that he sprinkled on the cemetery here, he made it the most sought-after burial ground in all of 13th-century Bohemia. When the plague came in the 14th century, the influx of bodies became unmanageable, and the ossuary was constructed in around 1400 to make room in the fast-filling cemetery.

In 1870 a notable family in the area appointed local artist and carpenter František Rint to reorganise the chaotic, full-to-bursting chapel. He created a macabre wonderland, making works of art from cleaned and polished human bones: the notable family’s coat of arms, an ornate chalice, and the proud artist’s signature spelled out in bone. Garlands of skulls festoon the arches surrounding the crowning masterpiece: a vast, ornate chandelier that uses every bone in the human body.

Paris Catacombs

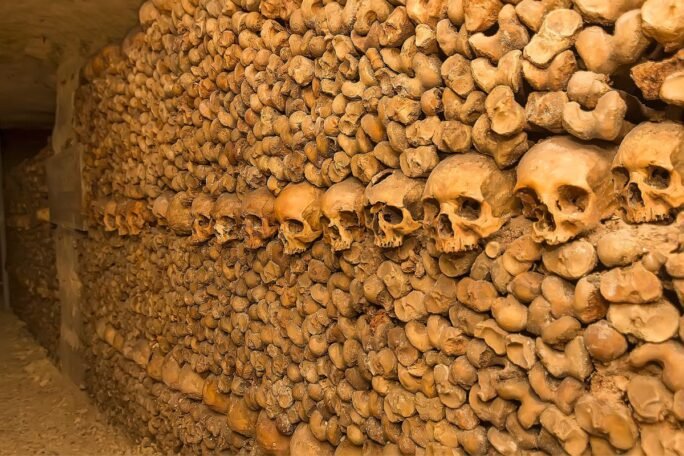

The story of Paris’ Catacombs is a tale of urban overcrowding. By the late 1700s, the city’s medieval cemeteries were bursting at the seams, making life increasingly unpleasant for nearby residents: undrinkable well-water, noxious smells and the occasional resurfacing of buried corpses. A solution presented itself in the 241km (150 miles) of disused limestone quarries that underlay the city streets. Beginning in 1785, the bones of between six-and seven-million people – the oldest dating back over 1200 years – were moved five storeys underground. It took 12 years.

By 1860, when it finally closed to burials, the Paris Municipal Ossuary had already become a popular tourist attraction. It had opened to the public in 1809, with a touch of macabre drama contributed by engraved signs such as ‘Arrête! C’est ici l’empire de la mort’ (‘Stop! This is the empire of death’). Part public health measure, part urban engineering feat, part sign of respect for the long-since departed, the Catacombs are now the world’s most visited memento mori, with over half a million annual visitors being reminded of the ephemeral nature of life.

Catacombs of Kom Ash Shuqqaf

Once Egypt’s capital city, Alexandria was dubbed the ‘Paris of Antiquity’, a multicultural melting pot and a vital crossing point between Asia and Europe. When an unfortunate donkey fell down a shaft here in 1900, it led to the discovery of an underground necropolis reflecting the interment traditions of three great cultures.

Used as a burial chamber from the 2nd to 4th centuries CE, the Catacombs of Kom Ash Shuqqaf are considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Medieval World. With sarcophagi for the placement of Egyptian mummies alongside niches for the remains of those who opted for Greek-and Roman-style cremation, the catacombs attest to the contemporary commingling of funerary traditions. And of art: on one tomb, statues of a man and woman are carved in stiff Egyptian poses, while the man’s head is chiselled in the lifelike Greek style and the woman sports an unmistakably Roman hairstyle. Also Roman is the triclinium, or banquet room, where relatives held annual ceremonial feasts to honour their dead.

Catacombs of Lima

A monumental complex in Lima’s historical centre, the Convento San Francisco is a jewel of Peru’s viceroyalty era. Inaugurated in 1672, the convent’s cavernous underground vaults were the colonial city’s first and largest cemetery, with up to 75,000 bodies estimated to have been buried here. When overcrowding became an issue, corpses were dissolved in quicklime, leaving only the skeletons.

Forgotten for over a century, the catacombs were rediscovered in 1943. They are said to be connected by subterranean passageways to the cathedral, other local churches and even the Government Palace. Some believe they may have been used during the Inquisition. Caretakers here took an artistic approach to the storage of their skeletal guests. Many of the bones are stacked in patterns – seen from the viewing grates above, they resemble mandalas, with skulls and femurs forming concentric rings. Other bones are classified by type and neatly stacked together, tibia with tibia, cranium with cranium.

Palermo’s Capuchin Monastery Catacombs

When brother Silvestro da Gubbio died in 1599, there was no room to bury him in the crowded cemetery of the Capuchin order’s Palermo monastery. So the monks began to excavate the crypts below. Initially only for deceased friars, burial in the Catacombe dei Cappuccini became a sign of prestige, the costly upkeep of the bodies payable only by the wealthiest citizens.

Over the years, the monks perfected the art of preservation: bodies were dried in special rooms, bathed in a vinegar solution and stuffed with hay. Mummification was a way to keep the dead close, says Dario Piombino-Mascali, archaeologist with the Sicily Mummy Project. “In Sicily, death has always been part of life. For centuries many Sicilians used mummification to make sure there was a constant relationship between life and death.” This ossuary with a difference is the final resting place for 8000 corpses and 1252 mummies, dressed up to the nines and displayed like life-sized dolls: hung from walls, perched on benches, set in poses. The halls are divided by category: men, women, virgins, children, priests, monks, professionals. Brother Silvestro da Gubbio is still there, greeting visitors at the entrance.

y or even through a ‘sky burial’. Through a Buddhist lens, death is a transition period, not the final curtain.