‘Hands up who feels guilty?’asked the charcoal-skirt-suited woman running the Working Mums seminar at a local preschool. Every hand in the room shot up. Every single woman – several having dashed there straight from work, still in their fitted blazers and patent black pumps; others, like me, delighted to be out after a day (all day) at home with the kids – was all flagging that she lives under the oppressive weight of Mother Guilt, feeling constantly remiss for not doing a good enough job. Except me. I didn’t put my hand up. Because I don’t feel guilty. Not one bit.

This is unusual. Mother guilt is a condition that usually afflicts a woman from the minute she gets pregnant, suddenly censoring everything she eats (no soft cheeses, pate, or sushi — to ward against an extremely rare bacteria, sure, but, really, what are the chances? Pregnant Japanese women devour sushi every meal and their babies turn out just fine). Then there’s guilt over the birth as we defend our epidurals and caesareans for being (in our heads) sub-par, as if it’s somehow our fault that we couldn’t pull off our biological imperative of giving birth ‘naturally’.

Then, when the baby arrives (whichever which way) the obsession with maternal diet shifts to infant diet, with guilt over breastfeeding. If mother doesn’t do it (whether by choice or because she finds herself unable to), guilt weighs heavily again.

And it goes on. Mothers feel guilty if we work, therefore leaving (by necessity)our little ones in someone else’s care. We feel guilty about not being a good enough mother for all sorts of reasons, from giving them processed cheese at the park (or, worse, a box of Jatz Crackers as I have done on several occasions) in lieu of tiny squares of watermelon, to too much time on the iPad (the kids, not the mothers) and talking on the phone or putting them to bed past eight pm.

Mother guilt is a fairly recent construct, a side effect of our preoccupation with perfect parenting. Listen to any mother and it would seem guilt – and its class-A co-symptoms anxiety and inadequacy – permeate modern motherhood so much as to become its underlying theme.

American writer and mother of four, Ayelet Waldman, (who, incidentally, feels no guilt for famously declaring she loves her husband more than her kids), reckons motherhood has become like an Olympic sport. Ever since mothers started going back to work we feel we have to make excuses for our choices. ‘I don’t know about your mother, but mine would basically open the door and say, “See you at dinner”,’Waldman said to The Guardian. ‘Now the stakes are so high, the way the game is played is such madness that how could we possibly do it all? The guilt and shame seems inevitable. How did we come to a point where not baking is a political act?

I don’t feel that way. I just don’t.

I don’t feel guilty about my caesarean birth, just relieved for getting there in the end, and thankful to live in an era where it was medically possible. I don’t feel guilty – just regretful – about stopping breastfeeding before I was ready; it wasn’t my choice. And even if it was, who cares? I don’t feel guilty about working two days a week. Rather I feel grateful that I get to sustain my career with minimal impact on my home life. While going to work with children at home (or, in my case, in childcare) might be another mother’s worst nightmare, her heart torn by economic necessity, it fulfils me and allows me to make use of the skills and experience I spent two decades amassing. Then, when I am with my two boys I’m not pining for another life.

I don’t feel guilty when I dish up chicken nuggets because they get veggies most other nights and sometimes nuggets are all I can rustle up after a frantic day. Too much TV? Doesn’t happen every day and it’s ABC4Kids, for goodness’sake, not Breaking Bad. Late to bed? They can sleep in. Skip bath? One night won’t hurt. No birthday party? So long as there’s cake. I don’t feel guilty about hauling them to the supermarket (we have to eat), bribing them with Tiny Teddies (how else to get two small kids in the car in a hurry?) or not teaching them to read or write their names (plenty of time for that).

Nor do I feel guilty when I go away. Sad, yes, and a little angsty, but not guilty. I’ve done it twice since my boys were born —a week- end wedding, and a meditation retreat. They could do with some Dad Time, I reasoned. And I could do with some time on my own.

Despite the show of hands that evening at the working mum seminar, I hardly think I’m the only one who feels this way. But you wouldn’t know it. Mother Guilt has become a status symbol of contemporary motherhood, something no mum wants to leave home without. We wear our guilt with pride – proof that if we’re in the throes of it we really must have a lot on our plates. We laugh off its ‘Bad Mummy’connotations, professing to be guilt-laden for heading to the office. But genuine guilt about how we mother isn’t funny. It’s a cry for acknowledgement. Or help.

Maybe most of us don’t feel guilty at all. We just think we should.

Guilt implies we feel bad about our choices, that we have our priorities all wrong, when perhaps we really don’t. Given proper consideration, maybe we’re actually OK with the calls we make. Our children will move on if we forget Book Week. It’s just that guilt has become the default position for mothers rather than its alternative: to give our- selves a break. To cut ourselves some slack.

To own up to guilt is like a get-out-of-jail-free card, exonerating ourselves for what we perceive as our mothering shortfalls. As Pamela Druckerman writes in French Children Don’t Throw Food, ‘For Anglo-phone mothers, guilt is an emotional tax we pay for going to work, not buying organic vegetables, or plopping our kids in front of the television so we can surf the web or make dinner. If we feel guilty, then it’s easier to do these things. We’ve ‘paid’for our lapses’.

Mostly I feel proud. Proud of myself for all I manage to get done in a day, quite chuffed at the incredible feats I pull off, juggling two exuberant puppy-like boys (nothing, I know, compared to many families), domestic drudgery and, on some days, a job too. It’s amazing there’s dinner at all. When I roll them into bed at night, I feel quite triumphant. I mean, have you seen the size of them? They are happy boys and I play a big part in making them so. No guilt. Just gratitude.

It doesn’t mean I don’t stuff up. I yell. The neighbours heard me recently losing it over a kerfuffle over a lost shoe. I rant, I nag, I snatch. I have sent ouroldest one to his room when I couldn’t handle the heat. But that doesn’t make me deficient. Just normal. It was only minutes before I came to my senses and went down to cuddle him. To be guilt-free doesn’t render me a better mother than those who are weighed down by it. It’s just that I accept I’m doing the best I can and I’m cool with that.

My friend, Anna, a working mum of three kids, is with me. ‘I don’t feel mother guilt at all’she tells me. ‘I’m absolutely solid that a) if something’s wrong the kids come first and b) I’m a much more interesting parent when I work. I’m sure the kids would pack me off to work if I stayed home full-time all the time!’she laughs.

Regret is different, I think. It’s where we wish we had done something differently but don’t necessarily feel bad about it (although it might hurt, still) or lug it around with us as we tend to do with guilt. Most parents know regret. For me it’s the small daily ones of my own making like losing my cool (I once hurled a nappy across the room – an unused one, I stress – in frustration. I regret it because I don’t want my boys to mimic my approach to stress release), or rushing the kids out the door with bribes and threats instead of hanging back and drawing the garbage truck like I’d promised. I regret the times (but can still make up for it, at least) where I said no to baking muffins because it makes too much of a mess. I have regrets over putting them into childcare an extra day a week to write my book. But no guilt.

Child psychologist Dr Angharad Rudkin listed the top five regrets of parents in an article in The Guardian where,not surprisingly, perhaps, ‘spending too little time with your children’got top billing. Not many of us is going to regret its opposite. The second top regret was ‘not prioritising their needs’, followed by ‘sweating the small stuff’, ‘taking short cuts’(i.e. parents who punish their kids without working through the underlying reasons for their angst), and, the fifth one: ‘feeling guilt’. Yes, guilt makes it into the top five most common parenting regrets. We regret feeling guilty!

To that end, Dr Rudkin recommends you ‘lower your expectations and be kind to yourself. Stop thinking about what you haven’t done and live in the moment.’

Perhaps guilt will come later for me. The teen years and beyond, when we fear it is we who caused their angst or waywardness or struggle to fit in. Then, I imagine, it might be tempting – yet futile – to draw a link between our priorities in their formative years with their grown-up view of the world. A latter-day beating up of our mother selves. I shudder to think of it.

A friend with three boys (including teenage twins) confirms my suspicions. ‘There is definitely more to be guilty about as the kids get older,’LJ assures me. ‘As an experienced mum you look back over a decade on things you wish you’d done differently. I felt guilty just yesterday when I left my little boy’s speech notes in the car so he had to miss out on being in the finals for a speech about what super-powers he wishes he had. And this was to be the first time he’d ever been brave enough to give a speech in front of the class!’

The day we talk, LJ’s colleague Lisa is feeling guilty for sending her eight-year-old to school that morning with a cold so she could get to work. ‘Mother guilt never leaves you alone,’she sighs, resignedly. ‘It gets you one way or the other.’

I am banking on love being enough. Boundless and unconditional love. Like the great majority of mothers the world over, I love my children to the moon and back, so much so that it hurts. They are top of mind always and I put them first, before everything. I protect and nurture them. I try to listen to them and hear them (two separate things), crouching down to their level and looking them in the eyes. I hold their hands where possible and go to them in the night (the nights when they’re not already sleeping beside me). I read them stories (caving in when they beg for ‘just one more’) and sing with them (persisting even in the face of ‘Stop, Mummy, my ears hurt’). No grounds for guilt in any of that.

‘Here’s my survey for worried parents’, writes JJ Keith in her memoir, Stop Reading Baby Books! ‘Have you washed dishes this week? Are you currently on crystal meth? Do you routinely use a car baby capsule? Yes, no, yes? Then it’s gonna be OK. If not now, then eventually.’

‘The Fear’, Blogger Mrs Woog calls it. She bashed out a post after seeing an alarming headline in a Sunday newspaper: ‘C-Section babies at higher risk of obesity’. ‘I read articles like this and automatically relate them to my own experiences as a mum and I have come to the conclusion that I am a total failure,’she wrote with her characteristic dry wit. ‘So to my darling boys: I humbly apologise if you grow up to be obese, slightly thick but vaccinated, and with a higher chance you will contract syphilis and gonorrhoea. I am sorry. You can totally blame me.’

I held onto an article I tore out of a magazine written by (then) dad-to-be, Giles Coren, a list of promises to his unborn child. I loved every item – like ‘I will never involve you in an argument I am having with your mother’, I will never take a teacher’s word against yours. Or anybody’s. Somebody has to believe you, always, unquestionably, no matter what’ – but especially this one about stuffing up, grandly, appealing to my new mother self:‘I won’t be obsessed with correcting the mistakes my parents made. We all make mistakes.. I will make plenty of mistakes of own. And I’ll just have to hope you forgive me.’

For many mothers guilt tracks far deeper: it’s an automatic response that is not so easy to shake off. It is what author Susan Maushart calls ‘that glass ceiling of the soul’holding women back from their full potential. In her book What Women Want Next she describes her reaction on hearing a speaker tell working women to ‘get rid of guilt’. ‘“Get rid of guilt”? Just “Get rid of it”!’she exclaims. ‘To me, it was like telling an audience of heroin addicts to just take up knitting.’

Or we could take up Buddhism. Buddhists do have a way of getting rid of guilt. (There isn’t even a word for guilt in Tibetan.) In her book, Buddhism for Mothers of Young Children, Sarah Napthali describes the antidotes to guilt as kindness towards ourselves, and forgiveness. Instead of guilt, which has no end, Buddhists practise remorse, which is far more constructive. ‘Remorse is followed by forgiveness and letting go whereas guilt tends to lead to ongoing anger towards yourself, a lack of forgiveness and, for some strange reason, repetition of the action that caused the guilt in the first place.’

Remorse I know too well. Because there was the time our baby fell off our balcony. I took my eyes off him for a second, the railing loose, and we nearly lost him, my screams piercing the neighbourhood. I flew so fast to the bottom it was as if angels were carrying me; I scooped up my baby, lifeless like a doll, too quiet for my liking, his eyes closed, his head muddy from his landing spot (I will be forever grateful for the mud that softened his fall) and I thought that was it. ‘Please, please, please,’I bargained with the gods. ‘Please be OK! Please!’His dad raced him to the hospital (in hindsight we should have called an ambulance but we weren’t thinking clearly in our anguish) while I stayed with his brother, and we comforted each other in our distress, he in a right state from witnessing his mother’s blood-drained terror. ‘Mummy scream!’he kept repeating. ‘Ahhh, Mummy sad!’he said, clumsily patting my head. He eventually dropped off in my arms in bed beside me, while I stayed up half the night waiting for news.

His dad texted updates throughout the night: Oh, the relief at being given the ‘all clear’. It was just a tiny hairline fracture on the back of his skull, which could have been so much worse were it not for the mud. But still he spent the next few nights in hospital ‘under observation’. ’You are very lucky,’said the young neurosurgeon. He was very kind, but warned gravely, ‘This much —’(his thumb and forefinger poised a fraction apart) ‘—in either direction and it could have been a very different outcome.’He followed with a lecture to watch my baby closely, saying he couldn’t handle any more falls.

I sobbed quietly while he spoke, feeling like the bad mother who had let down one of the ones I love the most, and who I had vowed to look after forever. I didn’t intend there to be any more falls. Just as I didn’t intend there to be this one. I blamed myself for turning my back (ironically to open the ‘baby gate’for a friend); his dad blamed himself for not securing the railing as he’d been meaning to. And I knew this had been my one chance. I had been let off this time, but that might not happen again.

One afternoon in the kids’hospital whilemy baby was sleeping, I ducked outside to the little garden dotted with fairies and elves dedicated to children who had died, leaving their parents in despair, and I prayed (in my own fashion). I closed my eyes and I thanked god (god being the universe and spirit and higher powers) for giving me my beautiful boys in the first place and for letting me off the hook for not taking proper care, as I had promised when they were born. I pledged to watch more closely, to be more vigilant, to be a better mother. To make the most of the opportunity I’ve been given to love (and be loved), to nurture and guide these precious little men and show them the way. My gratitude was overflowing, and only heightened by the reminders surrounding me in the ‘Fairy Garden’of mums who’d had to let go too soon.

For weeks afterwards (and still now) I howled with relief that my little boy survived; it is has coloured every day of his precious life since. But the remorse. That might never leave me.

Perhaps that’s why I don’t equate mother guilt with anything less than such a life-threatening moment. Like going to work. When you bear the weight of a near miss like that, it’s impossible to see it as being on par with pizza and Peppa Pig.

The only proof we will ever get that we have done good by our children is that they still love us when they’re older, when their love is more of a decision than a biological necessity of physical and emotional nurturance. Even better, if the best parts of us live on in them – our compassion, kind-heartedness, affection, wisdom, and unconditional love woven intrinsically into their DNA, making up who they become, shaping their character. It won’t be the times we left them with a babysitter, or fish fingers for dinner three nights in a row (I made sure there was broccoli too) or forgetting to pack their running shoes in their school bag. Or not being there to catch them when they fall. It will be our loving presence. Hugs and stories and holding hands as we walk. Playing I-Spy in the car, Thomas the Tank Engine on a rainy afternoon, star jumps on the trampoline. That will override the rest of it, the day-to-day stuff where we all fall short. The regrets.

‘Do you ever meet parts of yourself you don’t like as a parent? A bit crankier, a bit meaner?’ Psychologist Robin Grille asks a room full of new parents at a talk he was giving.‘There’s more love in you than you thought you had, you know. You give more than you ever thought you could give. We get stretched. We get opened up.’

Love is powerful enough to cancel out guilt. I know. I have tried it. That is what will stay with our children – the love – so it may as well be what stays with us too.

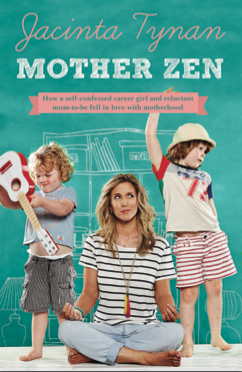

This is an edited extract from Mother Zen by Jacinta Tynan – Published by Harlequin.

Mother Zen by Jacinta Tynan (Harlequin Australia) is available for purchase (RRP $29.99) here or in all good book stores nationally.